Dahn Memory Lane: Why a Pittsburgh Heiress Jilted An Italian Count

Virginia Montanez uncovers the tale of Charlotte Elizabeth Howe who promised to marry an Italian Prince, but changed her mind just as he was arriving in America.

It’s a tale older than the Hallmark Movie Channel — a dashing prince, exasperated with a train of doe-eyed romantic hopefuls from connected families, falls for an American woman and makes her the princess of a fictitious mountainous principality with a name like Eastern Vasaria. So numerous are these formulaic tales that, by now, surely an AI application exists, capable of writing the script for the next one faster than you can say, “You have absconded with my heart” without gagging just a little.

But what if there was a twist?

What if the American became engaged to the royal, but, just as the wedding planning was ramping up, she secretly married her childhood sweetheart, rejecting the title and everything that came with it?

Who needs the saccharine Hallmark Movie Channel when you have real Pittsburgh history?

Curl up with a warm beverage as I tell you the tale of Elizabeth Howe and her jilted Italian count.

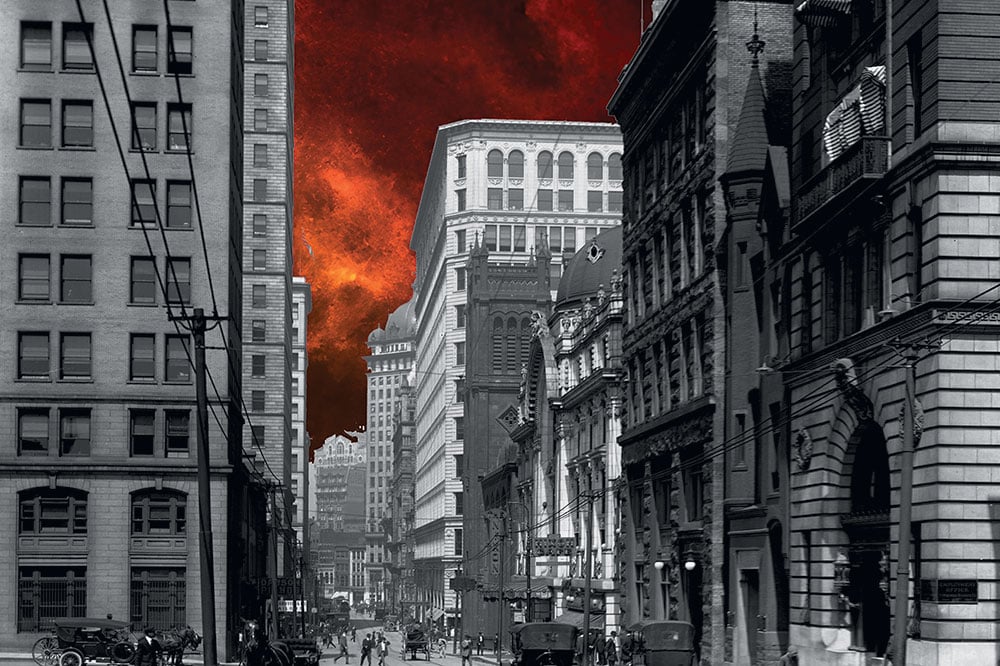

To a royal family ensconced in Rome, she would have been considered a commoner, but Charlotte Elizabeth Howe was far from common. Known as “Bessie,” she was a Civil War baby boomer, born in Pittsburgh in 1866 to Alice Kennedy and William R. Howe, a decorated Union captain. Bessie’s childhood years saw her father move on from the military toward business interests, which for a few years took the family to Corry, Pennsylvania. When Bessie was 11, the family welcomed her sister Florence, and a return to Pittsburgh was made. What awaited them wasn’t just the promise of a growing city but a double tragedy that would shape any teenager’s life.

At just 15, Bessie lost her mother Alice, aged 36, and four years later, 7-year-old Florence died of diphtheria, leaving Bessie and her father alone to navigate the growing social scene in a city where wealth was being earned in historical amounts.

Under headlines like “Gossip of Society” or “Movements and Whereabouts,” local columnists reported on events Bessie attended, where she summered, to which charities she gave time and money, and even when she took ill. But Bessie was far more than parties and patronage; from her early 20s, she was known for being smart, well-read, and an accomplished outdoor athlete.

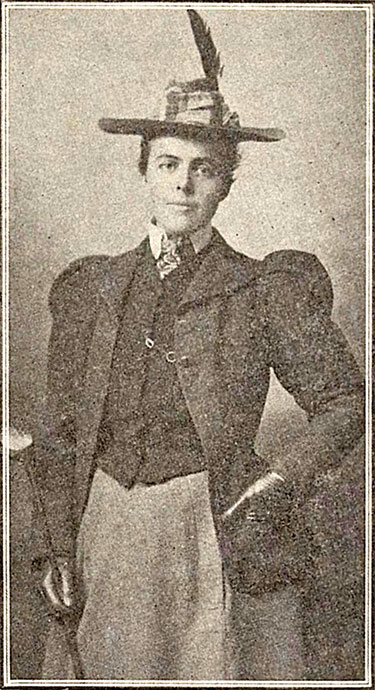

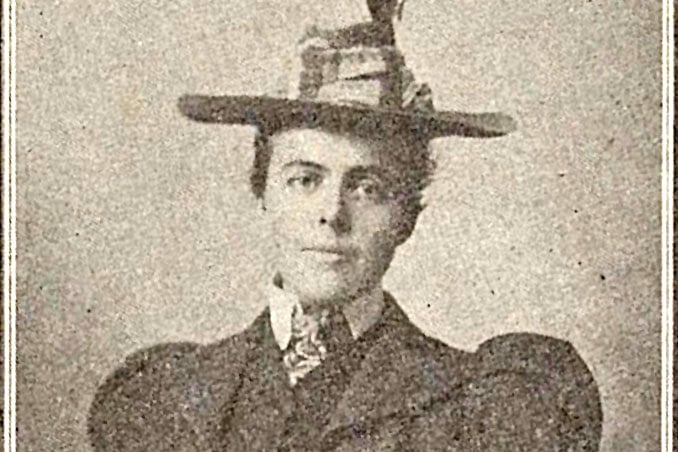

She was at ease with a cricket bat in her hand or astride a sprinting horse, tearing breakneck through the Pittsburgh countryside on an organized hunt. Most notably, she was a scratch golfer, regularly winning tournaments — in a frilly blouse and a skirt to her ankles, mind you. Perhaps she eschewed having her photo in the society pages, for there is but one published photo to be found of Bessie, posing in golf attire for The Pittsburgh Bulletin. She sports a high-collared shirt and tie, a buttoned vest and a fitted jacket with puffed sleeves over a pleated skirt. A feathered wide-brim hat sits atop her dark hair, her eyes piercing and her jaw strong. With a Mona Lisa smile, she speaks wordlessly of strength and pride. One leather-gloved hand casually rests in her pocket, the other loosely holds the shaft of her upturned wooden driver.

This photo of Bessie ran in June of 1899, the same month she lost her “big-hearted” father to diabetes complications, leaving her the sole heiress to the family fortune. At 30, she left behind “Bessie” and became Elizabeth.

As Pittsburgh’s richest eligible woman, Elizabeth seemed in no hurry to settle down, instead remaining devoted to the cause of increasing the popularity of outdoor recreation in the city. Thus in September 1904, when her engagement to Count Carlo de Cini of Rome — a grandnephew of Pope Leo XIII — was announced, a “thrill of excitement” rippled through Pittsburgh.

One particular headline might actually be a Hallmark movie title: “To Wed a Count.”

Papers across the country reported the surprise engagement, often referencing Elizabeth’s age. She was 38, certainly an “old maid” by societal rules, and the count was younger.

It is from here that gossip fully takes over, the truth nearly impossible to pinpoint. Upon the count’s return to Italy, the rumor mill claimed by November that the engagement was off, forcing Elizabeth to push back against the false reports. Columnists wrote confidently of the count’s monetary demands, hinting that he was essentially selling a title. From there, the society pages claimed a falling out had occurred and the wedding was surely off, while others insisted it remained on.

Whatever the truth, in late February 1905, in high spirits, Count Cini sailed for America with the intention of wedding his fiancée. He arrived in New York City’s harbor on March 1 and was immediately informed of the news: his fiancée, less than 24 hours earlier, had married her childhood friend Frank P. Sproul, a Pittsburgh lawyer of “modest means,” in a small private ceremony in a Pittsburgh church. Not only that, the newlyweds were sailing out on a ship from the same port, just as the count’s ship arrived.

Shocked and highly embarrassed, the count slipped away to avoid reporters seeking comment. “Italian Count Loses Fiancé,” “Count Cini Too Late” and “Jilted an Italian Count” were just some of the national headlines that surely won’t become Hallmark movie titles. The stories were rife with lies and speculation about money squabbles, lawsuit threats, and the count’s rumored insistence to his future bride that he would only remain faithful to her for two years.

The anti-Cini gossip reached a fever pitch as the new Mr. and Mrs. Sproul reached Europe, forcing the normally private Elizabeth to issue a statement via her lawyer, putting the rumors to rest. There had been no demands for money, she said. The count, by her telling, was an “honorable gentleman,” and she had sent written word to him that she wished to break the engagement, but the ship with her letter passed the count’s as he made his way toward America. The truth, she revealed, was that with the count away in Rome, she reconnected and fell in love with Frank.

Elizabeth and Frank did not get their happily ever after. They had two sons and relocated to Boston for their schooling, while maintaining homes and offices in Pittsburgh. Quite soon after their move in 1917, Frank fell down an open elevator shaft at the hotel where they were living. Their youngest son, Christopher, only 8, found him and sought help, but Frank died not long after, at age 53. At just 16 years old, Christopher drowned when his canoe overturned near his school in Windsor, Connecticut. His mother arrived to bring his body back to Pittsburgh for burial, but it would not be found for 26 days.

Tragedy struck again in 1932 when her eldest son, a recreational pilot, died in a single-engine plane crash near Boston. He was only 26, and his death once again left Elizabeth as the last remaining member of her immediate family.

Certainly, she was privileged, but money did not buy Elizabeth Howe lifelong happiness. The years on the gravestones of her family at Allegheny Cemetery speak to the losses she suffered until her death at age 68, just two years after her oldest son perished. She rose above the expectations of Pittsburgh’s society pages, choosing the life of an unconventional sportswoman who remained single until nearly 40. Perhaps the pain of her lifetime of losses kept her grounded as she navigated her seemingly charmed life, but her true story is one of grief, loss, and strength.

Bessie’s story isn’t a Hallmark story; it’s a Pittsburgh story of the daughter of a Civil War hero who grew up to soldier through everything life threw at her, grabbing on to love and happiness where she could find it amid shattering pain — and tossing away a tiara she knew she’d never wear.

In her column, Virginia Montanez digs deep into local history to find the forgotten secrets of Pittsburgh. Sign up for her email newsletter at breathingspace.substack.com