Dahn Memory Lane: Why Pittsburgh Is Spelled with an H

Virginia Montanez explains how from the first days of her life, Pittsburg(h?) has had a complicated name.

There’s a narrative we’ve been sold as Pittsburghers. Lore, even. It goes like this:

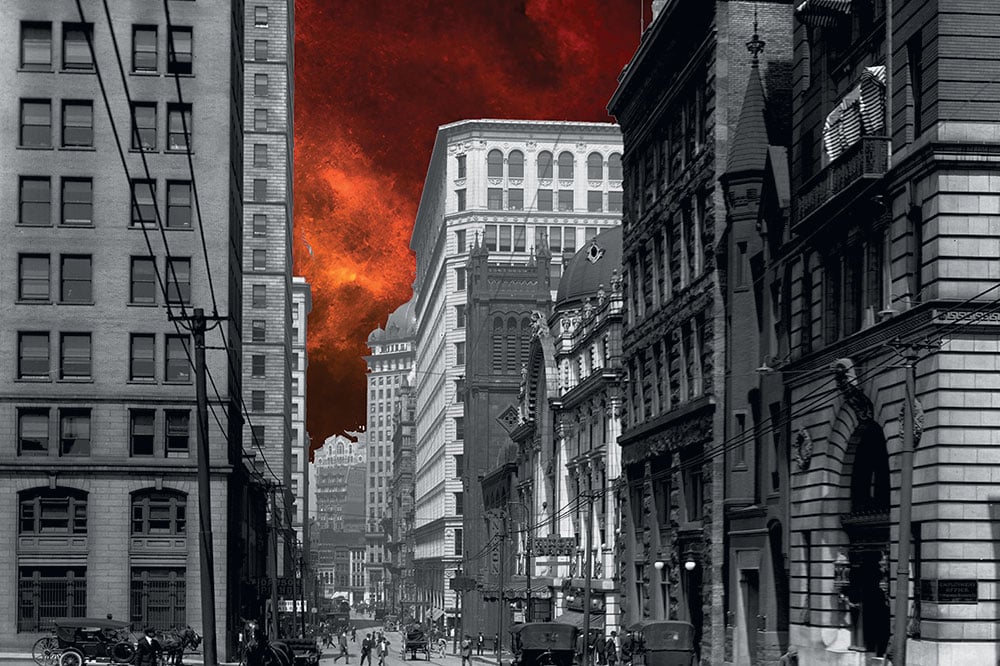

Once upon a time, there was born an American borough given the name Pittsburgh with an H. All of the people loved that H dearly, for it was a point of pride. As time passed and other towns decided to give away their Hs, Pittsburgh held desperately to hers. Her H made her special, after all. You could have her H on the fifth of Never at the strike of nope-o’clock.

But then one day, mean Mister U.S. Board on Geographic Names stole her H. Pittsburg’s dejected townspeople watched forlornly as their beloved silent letter disappeared from newspapers and business names overnight. She spent decades pining for her lost letter, begging those who took it to give it back. And then, like magic, they did. Pittsburg and her H were reunited and great joy and celebration spread across the lands at the confluence.

Blah blah, ever after, the end, roll credits.

This is a lovely story that follows the most common fiction archetypes along a standard fairytale plot.

Too bad it isn’t true.

Rest assured this fairytale has some basis in fact, but the full story is far messier than the Disney-fied version we’ve grown up with. Time for a little mythbusting, historian style.

We can at least say with absolute certainty that Pittsburgh was born with an H in her name, right?

Eh. It’s complicated.

When Pittsburg(h?) was named in 1758, it wasn’t named via just one piece of correspondence. Rather, John Forbes had at least two letters drafted, likely via dictation as he had been ailing for some time. His letters announcing France’s abandonment of Fort Duquesne and the naming of the new borough were dispatched to its namesake, William Pitt in Britain, and to Lt. Gov. William Denny of Pennsylvania.

The Nov. 27 letter to Pitt indeed has an H, but it’s wedged up against the 2 in the date, indicating that the writer, copyist or someone else entirely had inserted it after the fact, perhaps as a correction. That would easily settle the debate, had not the letter to Denny one day earlier omitted the H. So from the first days of her life, Pittsburg(h?) had a complicated name.

In 1786, the first issue of our first newspaper came off the press with a masthead of The Pittsburgh Gazette, but newspapers in the rest of the young country merely picked their favorite spelling and stuck with it. Things were no clearer when the Pennsylvania General Assembly seemingly incorporated Pittsburgh as a town with an H in 1804, but as a city without one in 1816. The official city seal included an H, as did the minutes of the first city council meeting that same year, but the official county map drawn up in 1817 left it off. Thus, it’s safe to say there wasn’t a generally adhered-to spelling of Pittsburgh for a long while, and that would remain the case well into the late 19th century.

How confusing was this locally? Picking a random date, say March 2, 1889, two years before the geographic board adopted “the dropping of the final ‘h’ in the termination ‘burgh’” in all government publications and maps, a Pittsburg(h)er could buy from the Downtown newsboys an issue of The Pittsburg Dispatch, The Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, The Pittsburg Press or The Pittsburgh Post. In light of this disunity, when the spelling was officially set as Pittsburg, the H became the subject not of great mourning, but great debate.

After the Pennsylvania Railroad decided to drop the H in 1891, an Ohio newspaper reported that “the people of that city [are unable] to agree as to whether there should be a final ‘h’ or not.” Meanwhile, the Pittsburg Dispatch took a victory lap, writing, “The Pennsylvania Company has sensibly decided that Pittsburg can get along without its final ‘h.’ The Dispatch discarded this superfluity long ago. Next!” The Pittsburg Times agreed, insisting in 1892 that the H was gone and there would be no further discussion as it “might rouse anew … the cranks who have made life a burden with arguments on this subject.”

One Pittsburgher, in a letter to the editor of The Pittsburg Press, declared that the H-spelling was passe and “wears the whiskers of time.” A staid opinion when compared to a note printed in the San Francisco Examiner in 1890 that demanded to know who “set the irritating fashion of writing Pittsburg with a final h. The name of the Cinder City at the fork of the Ohio is not Pittsburgh, but Pittsburg, and the man who first tacked on the final h is a person of high unworth whom it were Christian toleration to hang.” Such violence over a single letter! Alas, his likely target, John Forbes, had been in the grave for more than a century at that point.

A perfect example of the continued local disunity can be illustrated via one edition of The Pittsburgh Gazette (which never dropped their H) on March 1, 1902, a decade after the official respelling, wherein on the same page a Horne’s advertisement spelled it Pittsburg, but a Kaufmann’s advertisement went with Pittsburgh.

After a years-long campaign by the Chamber of Commerce, the H was officially restored by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names in 1911. Reactions were mixed. The Boston Globe called the H “useless” and its return “unfortunate.” The Daily Missoulian in Montana acknowledged that “there has never been either local or general uniformity,” but that the H spelling should be accepted because, “Pittsburgh has grown to be too important to be misspelled.” Finally, someone gets it.

In Pittsburgh, public sentiment had gradually shifted toward a stronger preference to revert to the longer spelling. In fact, there was a story told that a player for the Pirates, whose 1896 uniforms included the H, had “licked” a Chicago reporter in an argument over the spelling. No word on whether that involved fisticuffs or saliva, though. Devotion to the H even showed up during a sensational corruption trial in 1907. A wealthy society matron took the stand, and after stating she lived in Pittsburgh, was asked, “Pennsylvania?” to which she replied under oath, “It is the only Pittsburgh with a final H.” Case closed.

The H was reinstated locally by many after the 1911 decision, but there were holdouts. Even in 1918, there were still many businesses omitting the H in their names and advertisements. Society magazine The Pittsburg Bulletin still had not included the H come 1913, and The Pittsburg Press refused to become The Pittsburgh Press until 1921.

But the most stubborn of all the anti-H-ists wasn’t even in Pittsburgh — The Altoona Tribune decided they had a horse in a race happening 90 miles away. Weirdly aghast at the restoration of the old spelling, the editors insisted the H in Pittsburgh had Scottish origins and was therefore “foreign and unfriendly” and “a verbal monstrosity.” How a silent letter could be a verbal anything is anyone’s guess. They stubbornly spelled the city without the H until their final paper came off the presses in 1957.

The story of Pittsburgh’s H was long ago mythologized into a neat package. The truth is that Pittsburgh didn’t band together around her H. Never marched united into battle to rescue it from villainy. Never welcomed its return with collective open arms. The real story is both simpler and more complicated: From day one, no one really knew how to officially spell Pittsburgh, and so for over 150 years everyone spelled it however they liked until enough time passed to allow a generally accepted correct spelling to be gradually adopted by all.

Except poor spellers and those jagoffs in Altoona.

The end.

In her column, Virginia Montanez digs deep into local history to find the forgotten secrets of Pittsburgh. Sign up for her email newsletter at: breathingspace.substack.com.