Dahn Memory Lane: We Took That Personally

Virginia Montanez runs down some of the fiercest insults lobbed at Pittsburgh over the years.

To publish insults directed at the City of Pittsburgh is to unleash a flood of yinzer anger unseen since Sid Bream slid “safely” into home plate.

When Pittsburgh appears on a “Worst City for …” list, swaths of residents turn into statisticians arguing confidently about base-rate fallacies as if they didn’t just learn the phrase in a 30-second Google. We can criticize everything about ourselves, from our air quality to our persisting racial inequalities — and we often do — but if you badmouth us? You, from Boston or Philadelphia or Baltimore?

Heap praise upon us or git aht.

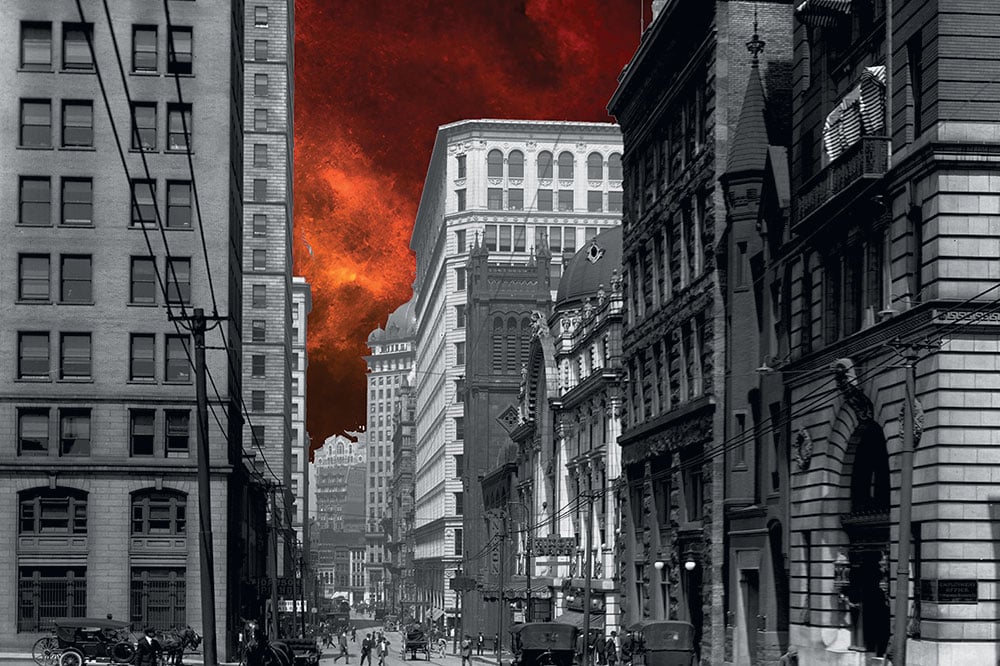

Reading in an out-of-town newspaper that Pittsburgh contains “nothing but dullness, stupidity and wickedness,” or that visitors found it “fearfully smutty” and “the ugliest city in the country,” is sure to rile the proverbial yinzer mob into grabbing their front-porch snow shovels, hellbent on exacting justice.

There’s just one problem; the insults in the preceding paragraph were published in 1843, 1872, and 1905, respectively. Put down the snow shovel and fire up the time machine, because history is full of insults that spared no corner of our city or its residents.

Pittsburgh was still a wild child when one of the earliest insults was printed. The year was 1792 and a military officer who arrived at the forks with a company of recruits dispatched a letter to his friend that included the oxymoronic statement, “I am agreeably disappointed in this place.”

After describing the beauty of the confluence (yes, he used that word), the officer trained a critical eye on those inhabiting the 200 homes therein. “Ostentation,” he wrote, “seems to be the prevailing passion of the Pittsburghers; billiards lead many … astray, and cards are too often introduced.” This merely sounds like Pittsburghers already knew how to make their own fun in 1792.

From then on, the people of Pittsburgh remained a common target of nitpicking outsiders. The first industrial revolution came to a close with our city full of factories, mines, and mills — and the sky dark with legendary smoke. It was in this Pittsburgh, in 1843, that a correspondent from the New York Daily Herald described his visit to the theater house, where he found the crowd of locals to be “the most rabbish [unruly] looking and acting herd of rowdies … ever congregated.”

Theatergoers “decked out in ragged coats” with “very sooty faces” were accused of calling out to the performers by name, hollering and stomping along to the music so vigorously they “made the house reel in beating time to the music with their feet.” Excuse us for our enthusiasm for culture and our lack of enthusiasm for fashion; both continue to serve us well.

If it wasn’t Pittsburghers’ behavior or clothing, it was their faces: “cadaverous” (Minneapolis Star Tribune, 1875); their speech: “buzz-saw Pittsburgh accent” (Louisville Courier-Journal, 1898); or their spending habits: “They spend their money like drunken sailors and don’t care a hang who objects to their amusements” (Baltimore Sun, 1906).

If you’re keeping score, this adds up to Baltimore being jealous of us for more than 115 years now.

No manner of insult, no cast aspersion, no pithy barb did a whit to whip up the winds of reform in the city. When the temperance movement gained momentum, Pittsburghers’ penchant for unapologetically enjoying life and libations only brought further disgust from the Bible-thumping morals sector. A correspondent to a New York paper wrote, “The King of Terrors has a pretty fair prospect of getting a goodly number of sinners here” (1843), while a visiting Canadian politician found himself in a “city of sin, immorality and debauchery” (1879). Things were no better in 1894 when a Salvation Army nurse declared, “This is one of the worst places I know for drunkenness and debauchery.” It’s honestly remarkable that Pittsburgh didn’t just put “debauchery” in the city slogan to spite the morally outraged.

As the new century found its footing, scandal frequently rocked our bustling city at the same time industrialists, entrepreneurs and bankers were amassing historic wealth. Socially conscious progressives and religious leaders deemed Pittsburgh a den of sin, for surely where there is money, there is vice thriving beneath the approving eye of Satan. A newspaper in Pittsburg, Kansas boldly declared our Pittsburg(h), “Utterly shameless in [its] reeking rottenness” (1903).

It only got worse from there.

By 1906, the city’s sinful reputation was a regular topic of aghast editorials and self-righteous dispatches, many comparing the city of steel to a famous pair of biblical sin cities. Under headlines like “Pittsburg is Wicked…,” it was labeled “the Sodom of America and the moral plague spot of the world” (The Weekly Herald, Amarillo, Texas). A correspondent to the Fargo, North Dakota Daily Republican also compared it to Sodom and Gomorrah because he saw it as a scandal-ridden “murky mass of filthy and heathenish nastiness,” while the Portsmouth Star in Virginia declared our forebears “rude, offensive, and salacious” and full of “shameless vulgarity.” The city’s wickedness became so legendary that year that a preacher stood on a street corner in downtown Milwaukee and shouted of Pittsburgh, “Thou wicked city of smoke! Thou sinner among the cities of the earth! Naught has ever come out of thee but society women and filthy-minded men.”

For many an outsider, the largest criticism was that Pittsburgh, a city of a staggering 250 millionaires, was unapologetic about its wealth. Insults were tossed at our “made-while-you-wait millionaires” (Topeka Daily Capital), while a Baltimore correspondent, Eugene B. Heath, bloviated on Pittsburgh’s sins in a thousand-word screed, concluding, “Pittsburgh is full of disgracefully wealthy men.”

That wealth came from progress, labor and industry, and where there is industry, there is smoke. Lots of it. Whether Pittsburgh was more notorious for her sinfulness or her smoke, remains debatable, for her sinners were “legion” and her smoke “foully abominable.” Correspondents declared they “couldn’t see a square down a street” (Portland Daily Press, 1866) and that “the possession of a nose is almost a misfortune, for the city stinks” (1867). Jokes about the smoke became commonplace; one published groaner went, “Before the doctors can vaccinate anybody there, they have to cut their way through half an inch of solidified coal-smoke” (1872).

As for our roads — rising and winding within restraining landforms and waterways — the Minneapolis Star-Tribune reported them to be “very narrow and rather crooked and [they] generally run uphill” (1875). A Kansas rag printed, “The principal direction of the streets is up and down. They ought to discard the street cars and install elevators” (1909). We did. They’re called inclines — funiculars if you’re fancy.

Surely, after a century of insults and judgment, Pittsburghers reformed their ways, right? Recognized their immoral selfishness? Their unholy vulgarity? Their wicked wealth? We might ask the evangelist Billy Sunday about that. He descended on Pittsburgh in 1914, determined to save the hellbound city. Despite preaching to a reported 300,000 Pittsburghers during his stay, Sunday was only able to convert a measly 1,492. The sinful masses refusing to repent and change had Sunday “near the verge of a breakdown, cling[ing] to the pulpit to keep from falling as he prayed for strength.” Alas, as the Scranton Tribune-Republican reported, “Sin-ridden Pittsburg is the hardest evangelistic nut to crack.”

Put that on a shirt.

In hindsight, perhaps the critics needed a new paradigm rather than an old scripture. Perhaps they needed to look away from the 1878 published claim from an ex-pat that “the place has seen its best days.” Perhaps the rowdy good times were earned as respite from long hours of honest labor. Perhaps the city’s wealth came not from sin but from the ingenuity to turn her raw materials into useful products that improved the world. Perhaps the unapologetic pride was earned.

Perhaps instead of looking at the soot-covered, life-living, foot-stomping, profane people who walked and worked among the low smoke, those critics should have set their eyes on the gleaming skyscrapers in their own cities — built with Pittsburgh metals — that allowed them to walk among the clouds.

In her quarterly column, Virginia Montanez digs deep into local history to find the forgotten secrets of Pittsburgh. Sign up for her email newsletter at: breathingspace.substack.com