Dahn Memory Lane: The Unexpected Tales of Pittsburgh History

Did you know Mister Rogers' grandfather played a part in the construction of an emergency infectious disease ward to combat the Spanish Flu?

Sometimes a story just doesn’t take you where you think it will.

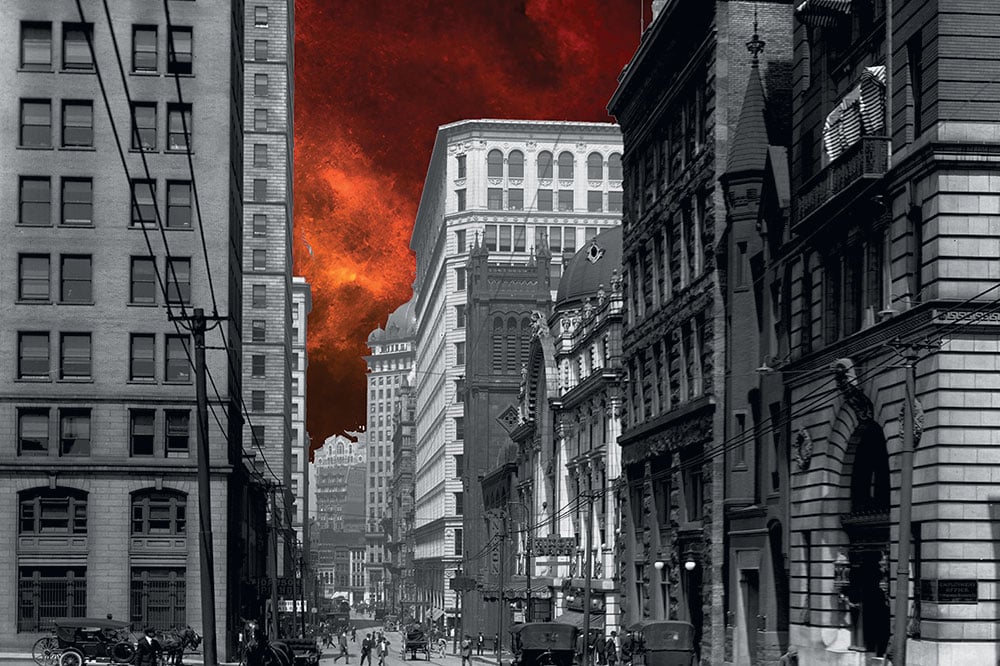

In the course of my research for this column, I’ve come across dozens of facts and tales about the city that I never would’ve guessed. Take, for instance, the “Spanish” Flu pandemic of 1918. The rampaging virus that killed upward of 675,000 Americans was an especially vicious menace to the Pittsburgh region. Having already spent the early part of September cutting down swaths of previously healthy young adults in Boston and Philadelphia, it arrived in the Steel City midway through the month. Here among the smoky skies and crowded working-class wards, it found a firm enough foothold to inflict the highest death rate across all major U.S. cities.

Pittsburgh’s undertakers were inundated with more bodies than could be processed and buried. Children were orphaned. Hospitals were so overrun that public health officials began transitioning other structures into makeshift clinics.

Related: Dahn Memory Lane: Why Pittsburgh Is Spelled with an H

Amid state-ordered business closures and bans on public gatherings, the virus made itself known in quiet Latrobe in early October with a handful of cases that weren’t seen as cause for immediate alarm. But Latrobe officials knew that there was a difference between remaining calm and being complacent — particularly in the face of an advancing epidemic. Seeing the havoc the virus wrought on hospital capacity in other locales, they made a decision: while the cases were still manageable, an emergency infectious disease ward should be erected at Latrobe Hospital.

One member of the hospital’s board was particularly forceful in urging the construction of the ward and took personal charge of the project, including supplying labor and building materials. Upon the ward’s completion, that board member remained on the logistical front lines of Latrobe’s response to the epidemic when cases inevitably spiked and the emergency annex filled up. That board member’s name was Fred McFeely.

Sometimes referred to as Mr. McFeely.

He was Fred Rogers’ maternal grandfather, after whom the television host was named and after whom he named the Speedy Delivery character who brightened up “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

That hometown legacy is just one of the “whoa” moments I’ve stumbled upon recently. Also in my “did yinz know” file: the story of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which originally stood Downtown where the Frick Building is today.

In 1901, the church essentially became a life-sized LEGO kit as it was dismantled piece-by-piece and carted by horse to Oakland, where it was meticulously reassembled at Forbes and Craft, every stone in its proper place. (The church was later demolished in 1990.) This relocation required the work of horses — because it occurred during the first years of the animals being replaced by automobiles.

If you think the newfangled, trapezoidal Tesla Cybertruck is a crowd-magnet, rest assured it has nothing on the reactions around Pittsburgh when the first “horseless carriages” appeared just before 1900.

It’s difficult to gauge who was more startled by the “devil wagons” — man or steed. The early steam or battery-powered conveyances were said to frighten the local horses “right out of their shoes,” to the point they’d “nearly break their necks” to escape the alien crafts that would race by at a “scorching” 25 mph. By 1906, it was estimated that 15% of Pittsburgh’s horses refused to leave their stalls each day, so paralyzed were they from fright.

The humans in the city maintained an identical measure of chill — nearly none. Any appearance of the new “electric chariots” on Pittsburgh’s streets sent crowds rushing to take in the strange sight. Police were called to quell gathering mobs who “shouted as though they beheld a miracle.”

One particular “miracle” first appeared on the North Side on May 1, 1899. For many, it was their first sight of the new machines, but this one was even more unusual than most — it had a big green pickle on top. Leave it to the marketing genius of H.J. Heinz to not only procure one of the first electric cars in Pittsburgh but to also have the foresight to turn it into mobile advertising. Used as a delivery wagon, the car was regularly so overwhelmed by gawking crowds that it could hardly operate.

Amusingly, horse-faithful Pittsburghers who encountered a horseless wagon during its early years were known to shout “Git a hoss!” at the driver as they motored by.

Show of hands in favor of bringing that particular bit of Pittsburghese back to our lexicon?

Hopefully, no such epithets were hurled when a small but still historically significant crowd gathered Downtown at the county jail on May 23, 1911.

There were more than half-a-million people living in the city at the time; cars were well on their way to replacing horses, and the Pirates had won their first World Series two years earlier. Amid this bustle of activity in a rapidly modernizing metropolis, 60 Pittsburghers gathered to witness the city’s final jail yard hanging. Deserted by his friends and relatives after his conviction for murdering his common-law wife, John Tyrie’s execution was witnessed by spectators, journalists and jurypersons.

It was an emotional affair, to the extent that a police officer collapsed shortly after the trap was sprung. Tyrie’s body remained hanging for nearly 10 minutes before it was cut down, and his death certificate notes the cause of death as a “broken neck caused by legal execution.” He is buried at Highwood Cemetery on the North Side.

Never charged, on the other hand, was a notorious criminal who terrorized the female population of Pittsburgh six years after Jack the Ripper appeared in London. The Steel City spent the year of 1894 contending instead with … “Jack the Chaser.” It is exactly as it sounds — a man, running after terrified women.

The jagoff (or jagoffs) first appeared in January, when one woman reported her chaser was clad in female attire. But later reports told of a culprit wearing an overcoat and a black mustache. Regardless, the villain, whose height was reported everywhere from 5-foot-5 to a hulking 6 feet, was dubbed Jack the Chaser by the local papers, with one news report musing, “When a young lady is pursued on the street by a figure of a gigantic female with outstretched arms, if her bangs don’t stand straight on end it is because they are false.”

For all the chasing, sometimes in broad daylight, Jack the Chaser never became Jack the Catcher, instead seeming to get his kicks from the chase itself. Regardless, Pittsburgh women remained vigilantly terrified, and for a time, some reportedly ran home screaming in fear of any unfamiliar man who approached. Like Jack the Ripper, Pittsburgh’s Jack the Chaser faded into the ether, never to be caught or identified.

From the ice wagons that provided free ice chips in impoverished, typhoid-stricken wards to the crypt inside Allegheny Observatory that serves as the final resting place of Pittsburgh’s pioneering astronomers John and Phoebe Brashear to the fact that the Downtown Kaufmann’s once featured a cupola topped with a 15-foot-tall statue of the Goddess of Liberty to the Pittsburgh Pirates player arrested during the Homestead Strike, Pittsburgh history never fails to offer surprises to those who spend hours or careers investigating it.

It is in that history that we find the lost stories of bravery, sacrifice, justice, fear, and the most perfect comeback ever to be lost to time … git a hoss!

In her column, Virginia Montanez digs deep into local history to find the forgotten secrets of Pittsburgh. Sign up for her email newsletter at: breathingspace.substack.com.