The Secrets of 10 Pittsburgh Landmarks

Here is a look at some of the surprising, behind-the-scenes details of how the Steel City gained some of its unique features.

Carnegie’s Namesake Dinosaur

Dinosaurs were a public fascination in the late 1800s. Andrew Carnegie wanted a specimen for his new Carnegie Institute in Oakland, so, in 1899, he sent a team to Wyoming to find one.

American scientists in the 1870s first classified the long-necked dinosaurs diplodocus and apatosaurus, using fossils discovered during construction of the transcontinental railroad. Carnegie’s team found a specimen so enormous that the museum was expanded to fit it; the great dino’s bones sat in storage until enough room was made. Meanwhile, a framed print of the Diplodocus carnegii hung on the wall at the steel baron’s summer castle in Scotland, where it caught the eye of King Edward VII. Carnegie agreed to give the monarch a copy of the colossal fossil for the British Museum.

Cast in plaster from mineralized bones, the model diplodocus was shipped across the Atlantic in 36 crates, assembled on a custom-designed steel frame and unveiled to great fanfare in 1905 (two years before the original went on display in Pittsburgh). Soon, more cast copies made their ways to museums in Berlin, Paris, Vienna, Bologna, St. Petersburg and Madrid. “Crowned heads of Europe all make a royal fuss,” went a popular ditty, “Over Uncle Andy and his old diplodocus.”

The world’s most celebrated dinosaur skeleton also was used as the model for the full-size statue, nicknamed “Dippy,” hulking over Forbes Avenue outside the museum. Its head has always been something of a conjecture; no one has ever found a complete diplodocus skull. In 1915, when Carnegie’s bone hunters discovered another near-complete sauropod skeleton in Utah, he named it after his wife: Apatosaurus louisae. Both stand in the museum to this day, reminding visitors that dinos are a girl’s best friend.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 4400 Forbes Ave., North Oakland

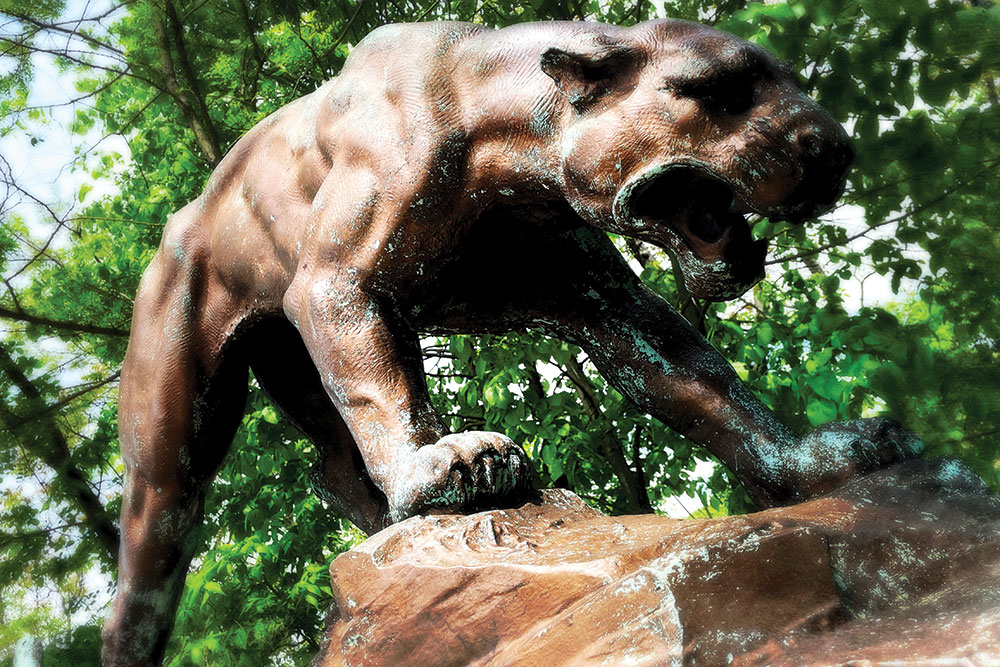

Panthers of Pitt

The four bronze panthers that prowl the ends of the Panther Hollow Bridge are the original inspiration for the University of Pittsburgh’s mascot. Their creator, Giuseppe Moretti, completed several prominent commissions for the city between 1895 and 1900. He was at the time the sculptor of choice for Edward Bigelow, the city’s powerful director of public works.

Surely counting in the Italian’s favor was his first Pittsburgh commission, a larger-than-life bronze likeness of Bigelow in front of Phipps Conservatory. Initially proposed by Republican political boss William Magee, the sculpture honors Bigelow’s work establishing Schenley and Highland parks.

That a public official would allow a monument of himself to be raised while still serving in office says something about Bigelow — and about the times. The director wasn’t easy to please; he rejected Moretti’s first effort because of an incorrectly curled mustache and an excessively protuberant chin.

Once the boss was placated, Moretti won further Pittsburgh commissions, including the sculptural group at the entrance to Highland Park, the bridge panthers and a likeness of Stephen Foster. A planned grand entrance to Schenley Park was canned when Bigelow briefly fell from power. Business leaders in Birmingham, Alabama, later hired Moretti to create the world’s largest cast-iron statue, a 56-foot model of the Roman god Vulcan, to represent their city at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. It now crowns an observation tower on a mountain ridge overlooking the city once called the “Pittsburgh of the South.”

Panther Hollow Road (near Phipps Conservatory & Botanical Gardens), Central Oakland

The Trio with Brio

Pittsburgh’s “City of Bridges” title owes much to the three graceful structures spanning the Allegheny River at Sixth, Seventh and Ninth streets. Now named for Roberto Clemente, Andy Warhol and Rachel Carson, the “Three Sisters” bridges combine sophisticated engineering with an elegance that won the accolade of “Most Beautiful Steel Bridge” from the American Institute of Steel Construction in 1928, the award’s inaugural year.

They weren’t supposed to be so fetching. When the U.S. War Department forced the city to replace three existing spans to improve river traffic clearance, their proposed replacements were boxy, run-of-the-mill truss bridges. But the city art commission — a seven-man advisory body of artists and architects — shot down the proffered plans as “inadequate and unworthy” and called instead for “structures possessing real artistic merit.”

Back at their drawing boards, county engineers cribbed a design from an innovative 1915 suspension bridge in Cologne, Germany. That structure used steel eyebars instead of cables to hold up its deck, with the eyebars anchored directly into the deck itself at each end rather than to anchorages in the ground.

The self-anchoring feature allows Pittsburgh’s three bridges to squeeze into a relatively tight landing space without obstructing traffic along Fort Duquesne Boulevard. They were the first American bridges of their kind and became an unmistakable Pittsburgh icon. Give credit to the art commission.

Fort Duquesne Boulevard at Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Streets, Downtown

The Scholastic Skyscraper

When John Bowman became chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh in 1921, classrooms were overflowing — the result of a postwar enrollment boom. His predecessor’s ambitious plan to build an academic acropolis on the Oakland hillside above Fifth Avenue had made little headway. Bowman switched course, calling for something completely unorthodox: a college skyscraper that would be dubbed the Cathedral of Learning; he made pitches for the necessary funds in the mid-’20s.

The Great Depression temporarily stalled work on the 42-story neo-Gothic tower, letting wind whistle through the girders of the bottom three stories. It was finally completed in 1937, with expert stonemasons carving and setting the blocks for the awe-inducing three-story vaults of the Commons Room. Pitt proudly boasted the world’s tallest educational building — until Moscow State University surpassed it in 1953. (The claim was modified to “tallest educational building in the free world.”)

The Nationality Rooms, designed and funded by committees made up of Pittsburghers from the represented countries, were overseen by Ruth Crawford Mitchell. A lecturer in the economics department who taught classes on immigration and assimilation, she had conducted surveys and reports for Bowman that revealed one in three students was a second-generation immigrant. Bowman sensed an opportunity to foster ethnic pride among those students.

“A hundred years from now, perhaps a thousand years from now,” Bowman wrote in one of those initial fundraising appeals, “people may look back, see through history these present days as the beginning of a new age, and say, ‘The first great expression of the creative-spiritual force that changed the world came into being at Pittsburgh.’”

4200 Fifth Ave., North Oakland

The World’s Oldest Incline

Hauling passengers up and down Mount Washington since 1870, the Monongahela Incline is the world’s oldest funicular passenger railway still in operation. The first incline ever built, which rose through a tunnel, debuted in 1862 in Lyon, France. But its tracks were pulled up long ago; today, it’s merely an uncomfortably steep car tunnel.

Budapest opened the world’s second, in 1869, for its royal castle. Like ours, it offered dramatic river and bridge views, but it was destroyed during World War II bombing and wasn’t rebuilt for several decades — costing it the “continuous operation” designation.

A native of Budapest, Samuel Diescher, built 10 of the 15 passenger funiculars Pittsburgh once hosted. That tally includes the Duquesne Incline, as well as a huge one that soared over the Strip District’s railroad yards to the Hill District. The former tracks of another occupied the site of the precarious stairs that today climb the Bluff to Duquesne University above a roaring highway.

After a funicular railway was built to haul tourists to the crater atop Mount Vesuvius in 1880, a local song celebrating it turned into a worldwide smash hit of remarkable staying power. “Funiculì, Funiculà” in the Neapolitan dialect translates to “Let’s Incline Up, Let’s Incline Down!” Diescher had a house on Mount Washington, and one imagines him singing the famous incline song while commuting to the city. Hum a few bars the next time you’re riding up to Grandview Avenue.

Upper Station: Corner of Grandview Avenue and Wyoming Street, Mount Washington

The Why of Fallingwater

Edgar Kaufmann loved to make a visual statement. In the 1920s, he spent lavishly on a Fox Chapel mansion and an exquisite, Art Deco overhaul of his Downtown department store. During the Great Depression, Kaufmann proffered a lifeline to Frank Lloyd Wright when he asked the aging architect — who was then mired in a career slump — to design a planetarium for the store.

That idea never took shape. Rival North Side store Boggs & Buhl did a planetarium instead, using a different designer. But Kaufmann had other requests for Wright. He wanted the architect to remodel his office. And — in a history-making development — he wanted a summer house for his family in the Laurel Highlands, on the former grounds of a Kaufmann’s employee summer camp.

Wright masterfully combined stone, steel, glass and cantilevered concrete porches into an assemblage that, while clearly modern, also seems to spring organically from the boulders and waterfall below. Fallingwater was finished in 1937, and the homeowner wielded his considerable talent for publicity to get it noticed. Wright and the house made the cover of Time magazine, and praise for his creation has never abated. More than half a century after Fallingwater was built, members of the American Institute of Architects voted it “the best all-time work of American architecture.”

Kaufmann had Wright draw up bigger Pittsburgh projects, including a Mt. Washington residential high-rise and a ludicrously massive, spiraling civic center complex that would have smothered Point State Park. None came to fruition, and Wright became embittered with his patron and Pittsburgh. But Fallingwater launched the 20th century’s most brilliant architect into a scintillating second act. A smaller, inverted version of his spiral design resurfaced in his Guggenheim Museum in New York City, while a flurry of smaller commissions included a house for the Kaufmanns’ neighbors at Kentuck Knob.

1491 Mill Run Road, Mill Run, Fayette County

Font of Inspiration

Converting 36 acres of railyards and sooty warehouses into Point State Park and its iconic fountain took many years of proposals and planning — and millions of dollars. The pivotal moment came in 1945, when Charles Stotz, the architect sketching a plan for the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, threw down his pencil in disgust.

“We’ll never get anywhere with those damn bridges where they are!” Stotz shouted to his partner, landscape architect Ralph Griswold. The aging Point and Manchester bridges touched down at the tip of the Golden Triangle, wrecking the sweeping vistas of the park the architects dreamt of; meanwhile, the approaching roads would surround their immaculate lawns with noisy traffic.

The men appealed to conference leaders, who took their case to Gov. Edward Martin. He agreed to back their plan to replace the bridges and promised state funds to build a park; original plans called for a rebuilt Fort Duquesne and partially rebuilt Fort Pitt, a small marina, and a fountain at the tip. It wouldn’t be the world’s biggest fountain — Geneva’s Jet d’Eau, which debuted in 1891, was almost twice as high. But it would become “the trademark of Pittsburgh, as the Eiffel Tower is for Paris,” Mayor David Lawrence predicted at a Harvard urban-design conference in 1956.

It wasn’t until July 22, 1974, that the fountain finally gushed for the first time, to the delight of locals as well as baseball fans in town for that year’s All-Star Game. It draws its supply not from the three rivers surrounding it, but from a “fourth river” — a mile-wide subterranean aquifer through which trickles a vast volume of water from the Great Lakes.

Park entrance on Commonwealth Place (near Liberty Avenue intersection), Downtown

The Crystal Palace

Philip Johnson’s most famous glass building isn’t PPG Place. It’s the stark Glass House he built for himself in New Canaan, Connecticut. But his Pittsburgh skyscraper is a noteworthy design by an architect who loved to shock the public.

Hailing from a wealthy Cleveland family, Johnson first made his mark as curator of architecture for the Museum of Modern Art, where he put on a 1932 exhibition launching the “International Style.” He later worked with minimalist master Ludwig Mies van der Rohe on the Seagram Building, regarded by many as the ne plus ultra of tall, glass filing cabinets. Eventually tiring of the austere slabs, Johnson caused a stir in 1978 with his pink granite Manhattan headquarters for AT&T, which featured a roofline resembling the top of a fancy bookcase.

A year later, when Johnson came to Pittsburgh to unveil his concept of a crenellated castle tower sheathed in glass rather than stone, the mayor claimed that it vindicated his urban renewal push. “PPG gives it all substance,” said Richard Caligiuri. “Renaissance II is for real!” Critics sometimes diss the building, which opened in 1983. “The romanticism is too sentimental, too easy — architecture made by Tchaikovsky,” sniffed New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger. Still, the city skyline is hard to imagine without PPG.

Such architectural quibbles pale in comparison to Johnson’s egregious past. During the Depression, he was a vocal advocate for fascism, even collaborating with the Nazis to promote their propaganda and writing anti-Semitic reports for a right-wing American publication. He recanted and joined the U.S. Army when war broke out; when it ended, Johnson went to graduate school at Harvard to become an architect. Last year, in response to his objectionable political leanings, Harvard removed Johnson’s name from a house he designed near campus.

One PPG Place (between Third and Fourth avenues), Downtown

A Steel-Mill Superman

Pittsburgh’s John Henry is Joe Magarac. As the legend goes, the steel-mill superman never slept, working 24 hours a day and 365 days a year. His last name means “donkey” in Croatian, and the mythical folk hero symbolizes the stoic Eastern European immigrants who labored in the region’s mills a century ago in the hope of better lives for their families.

According to some tellings of the tall tale, Joe was actually made of steel. That explains why the folksy statue of Joe Magarac at the entrance of the U.S. Steel Edgar Thomson Works in Braddock has skin the same color as the steel beam he is bending into a horseshoe shape. The statue, at least, really does have steel bones — the fiberglass sculpture is molded around a steel skeleton.

It is the largest of about 30 life-size figures Mary Ann Spanagel and her sister, Tracy Lee Simmen, created for the “Old Mon Railroad” at nearby Kennywood Park in 1993. The two also built themed floats for Kennywood Park’s annual fall fantasy parade for several decades. They made their last floats in 2008; the following year, their sculpture was moved from Kennywood to the mill across the Mon.

Spanagel, 75, says she is happy her Joe Magarac sculpture found a new job. It reminds her of “that time of my life when we were being so productive, really enjoying the process of starting with nothing and making something,” she says. “It was just joyous.” PM

Braddock Avenue at Edgar Thomson Works entrance, North Braddock

The Temple on the Hill

The lovely sight of a gleaming white Hindu temple sitting on a hilltop has been delighting and surprising motorists on the Parkway East in Monroeville for almost five decades. Ground was broken in 1976 for the Sri Venkateswara Temple, which is modeled after a much older temple (sitting atop much higher hills) overlooking the southern Indian city of Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh.

One of the temple’s leading founders was Raj Gopal, an engineer in Westinghouse’s nuclear energy division who arrived in Pittsburgh in the early 1960s. He and other Indian immigrants used to gather and worship in the basement of a Squirrel Hill shopfront, leading Gopal and others to petition religious leaders in India for help in constructing a temple.

The white entrance tower, made of cement shaped like carved stone, was finished in 1978 — a year after the first Hindu temple built in North America opened in Queens. Paid for with contributions from Hindus across the United States (as well as the mother temple in Tirupati), the handsome temple is dedicated to Vishnu the preserver, one of the three central deities of Hinduism. Today, the structure has multiple functions as a gathering place for services, festivals and other community events.

1230 McCully Drive, Penn Hills

Mark Houser is a professional speaker and author of the new book “MultiStories: 55 Antique Skyscrapers & the Business Tycoons Who Built Them.” He is director of news and information for Robert Morris University, an antique skyscraper tour guide for Doors Open Pittsburgh and a regular contributor to Pittsburgh Magazine, including the recurring HOME feature This Old Pittsburgh House.