How Pittsburgh Restaurant Workers Count on Each Other

Pittsburgh Restaurant Workers Aid offers support to service industry employees.

LARISA MEDNIS, TAYLOR STESSNEY, CHRISTOPHER EDWARDS AND KACY MCGILL CREATE CARE PACKAGES

Pittsburgh’s decade-long restaurant boom ranked high among the city’s bragging points. Boosters touted its dining scene as a reason to come to Pittsburgh for conventions and tourism. “Where did you eat this weekend?” was a common question asked on a Monday morning at the office. Chefs had become local celebrities, with magazines such as this one devoting significant space to their handiwork.

The onset of COVID-19 and the ensuing closure of restaurants on March 16 put a hard pause on Pittsburgh’s culinary upswing. While many have reopened for takeout and some in a limited capacity (and with varying success) for on-premise dining, it’s now a different landscape. With no return to normalcy in sight, the prospect for full-time work in what labor analytics research firm Emsi named as the region’s largest employment sector in 2017 remains limited. The unsung heroes of those restaurants — servers, hosts, bartenders, line cooks and dishwashers — are among the labor force hardest hit by the pandemic.

To that end, a community that typically leans outward to offer a delightful diversion to others now is pulling together to help one another. That effort is led by Pittsburgh Restaurant Workers Aid, organized by Kacy McGill and Taylor Stessney.

“I messaged Taylor that night [the restaurants shut down] and said, ‘Should we do something about this?’ because I was seeing a lot of my restaurant friends freaking out about what was happening,” says McGill.

The next morning, they launched PRWA’s Facebook group, Greater Pittsburgh Restaurant Workers Mutual Aid; approximately 1,000 people signed up in the first 24 hours and the page now has more than 3,600 members. “When we first started, it was triage. We wanted to make sure we had an emergency fund for people who needed to pay an immediate bill or for medication,” says Stessney.

On March 17, PRWA launched a GoFundMe campaign that to date has raised more than $43,000 and supported approximately 500 restaurant workers and their families; the Pittsburgh Foundation also contributed $15,000 to the fund. Direct food assistance began immediately, too, with grocery donations and drop-offs sent out from a porch in Bloomfield. A team of volunteers delivered food to people’s houses. Establishments such as Monteverde’s Produce, Square Cafe and Commonplace Coffee took to the Facebook group to announce additional food donations.

Over the next few months, the emergency action grew into an organization built to sustain Pittsburgh’s service industry workers through an ongoing crisis. Food drives, resource pooling and information sharing are now the norm among PRWA members.

McGill, Stessney and the organization’s five volunteer board members meet virtually every week to discuss goals met the previous week and decide areas of focus for the forthcoming week. Every meeting, they say, means a different set of needs to address.

“We’re in this position where we’re trying to guess what’s going to happen in the next couple of days. We’re trying to anticipate needs, and I think we’re doing a pretty good job of it,” says McGill.

“The amount of time that people might be out of work keeps extending. Now that we don’t know how long it’s going to take for things to get back to normal, it’s about making sure there is a steady resource to help people who need it get through these times,” adds Stessney.

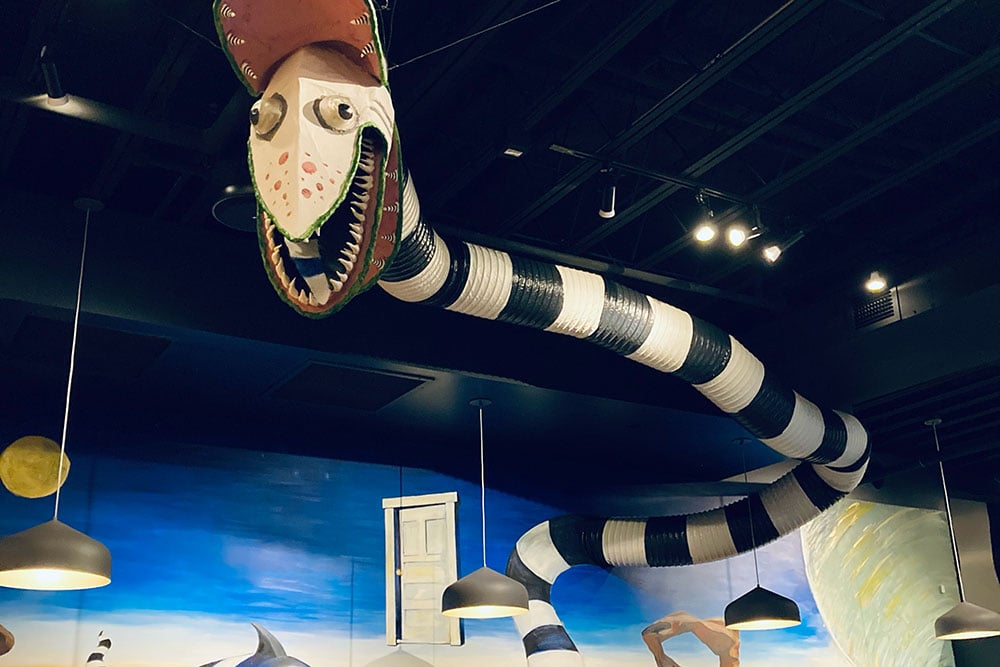

They moved the emergency food assistance hub to a room at the Irma Freeman Center in Garfield, which donated space for four months, and again in July to the current location at XFactory in North Point Breeze. Care packages are still delivered weekly to the homes of people who need them.

412 Food Rescue began distributing food to PRWA in April and its assistance continues with donations of approximately 100 meals per week; the hunger relief organization also helped with a significant financial contribution. The food aid isn’t limited to people, either — Hungry Hippo’s Pet Food Pantry (a program of Biggies Bullies) and Petagogy have chipped in with pet food. The Western PA Diaper Bank is there for restaurant families with young children, having donated more than 20,000 diapers since March.

As important as direct sharing of resources is the sharing of information and emotional support. Members of the group empower each other to address mental health needs with a network of check-in calls. Participants often pass on information about what’s happening in their professional networks.

“It’s mutual aid, and it’s community-focused,” says Elina Malkin, a bartender at tina’s in Bloomfield and PRWA board member.

Malkin says community members outside of the service industry have stepped in to help out-of-work restaurant employees as well. For example, she praises Barney Oursler, director of Mon Valley Unemployed Committee and a decades-long advocate for workers, starting with the collapse of the steel economy, for sharing guidance on navigating access to state and federal support programs.

The final piece of PRWA’s focus is, as people slowly return to work, partnering with labor-focused organizations such as the Pennsylvania chapter of Restaurant Opportunities Center United as a hub for worker advocacy. PRWA members are kept informed about topics such as what actions restaurant owners are implementing to keep employees safe, how to file for partial unemployment benefits and how to navigate the physical and emotional challenges of working with the public amid a pandemic.

“There is a fairly defined social contract of how you behave in a restaurant, just in the same way there is with a business meeting or social gathering with your family. Those rules have changed [with COVID], and people don’t know they’ve changed. And how would they? Right now, it’s almost entirely upon the people who are the least supported, making the least amount of profit and have the most to risk to try to teach people this new way of behaving in restaurants,” says Malkin.

“When people come into your place of employment and know that they can control what they can pay you at the end of the day [with the amount they tip], it’s a weird power dynamic,” McGill adds.

The focus on labor rights likely will be one of the more lasting actions of the group. “There needs to be more dignity given to us for our jobs. And better communication from the people who employ us,” says Stessney, noting that she learned she was laid off via an email sent at 11 p.m. on a Saturday.

For now, the immediate action of supporting service industry employees and their families through the uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic remains on the forefront. The group now has a part-time staff member to help coordinate the work at the distribution center. McGill says that PRWA is in the process of applying for 501c3 nonprofit status, and New Sun Rising has signed on as a fiscal sponsor.

“We’re still in a crisis period. We don’t know when this is going to end. We’re not even close to a recovery period. And I don’t know what that’s going to look like,” McGill says.