Chef Kevin Sousa Motors on with New Restaurants. Will They Last?

Sousa hopes to turn the page with his two forthcoming establishments. But a long history of similar promises made to previous business partners and communities raises questions about his projects’ longevity and the costs that may come with them.

In July, Kevin Sousa announced he planned to open two restaurants, Mount Oliver Bodega in Mount Oliver and Arlington Beverage Club in Allentown — his fifth and sixth restaurant openings (plus a bar) in a little more than a decade.

If these new projects existed in a bubble or if Sousa were running an established restaurant group, there’s reason to believe this is something we ought to be excited about — Sousa is a creative and talented chef who has delivered terrific restaurants to Pittsburgh.

These announced establishments don’t exist in a void. Mount Oliver Bodega and Arlington Beverage Club come with a track record.

It’s not wildly out of the norm for an ambitious restaurateur to launch a bunch of restaurants over a decade, even if a few of them don’t work out in the long run. This is a tricky, low-margin business, after all. However, Sousa’s record is of big promises for the restaurants he’s opening, which typically are in low-income neighborhoods, followed by complete disengagement. And then he’s on to the next big thing, the thing that he says truly speaks to what he wants to do.

Take this quote from a July article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette celebrating Sousa’s forthcoming restaurants. “For the first time, I’m getting emotional about food,” he said. “I smelled a pizza that I made last night, and it was the first real ‘Ratatouille’ moment.”

The following is the lead quote in his 2013 Kickstarter campaign for Superior Motors in Braddock, which raised $310,225 from 2,026 backers:

“For the first time in my career, I have the opportunity to breathe life into a restaurant that is not chasing trends, but a restaurant that has no choice other than to represent a Place and Time by producing food representative of its past, present and future.”

At the time, Sousa was executive chef and part owner of three restaurants: Salt of the Earth in Garfield and Union Pig and Chicken and Station Street in East Liberty. A little more than a year later, he’d be divested of all three.

Sousa isn’t a huckster or deliberate peddler of empty promises. His issue is that once he believes in the next new thing, he leaves a turbulence of debt — sometimes with public and institutional money that could have been used to fund chefs with fewer advantages or other works — and disappointment in the rearview mirror.

The latest disappointment is Sousa’s departure from Superior Motors, which he announced on Instagram in July (the same day he and his partners sent press releases announcing their new ventures). Sousa no longer has any ownership in Superior Motors. The nationally acclaimed restaurant remains closed, though its ownership group is committed to a long-term goal of re-opening the restaurant under new leadership.

“It’s clearly a pattern,” says Liza Cruze, one of the primary investors in Salt of the Earth, Sousa’s first restaurant, which opened in 2010. “Maybe he enjoys starting new things, and that’s what he’s good at. But he leaves a wake of destruction behind him.”

We reached out to Kevin Sousa multiple times over several weeks and all interview requests were declined.

Rub Salt on It

In 2007, Sousa was executive chef of Downtown’s Bigelow Grille, a position he’d held since 2005. He was a year into his first big spotlight project, a molecular gastronomy influenced tasting menu called Alchemy that functioned as a restaurant within the restaurant and was the toast of the town.

But Sousa was already casting his net elsewhere, in talks for a restaurant of his own. He left Bigelow in 2008 and worked here and there until that space for Salt of the Earth became available.

“We had the building. We thought a restaurant would be great there because we lived in [nearby] Friendship,” says Cruze, who runs Cruze Architects with her husband, Doug.

The Cruzes eventually stepped in as investors. They were joined by Sousa’s now-ex-wife, Holly, and two of the Sousas’ friends, Kristi Cooper and Alberto Vazquez.

Sousa shined at Salt of the Earth. He won accolades locally and nationally and the establishment is a transformational part of Pittsburgh’s culinary history. The restaurant launched or helped develop the careers of a generation of hospitality industry professionals. Did you know, for example, that Millie’s Homemade Ice Cream got its start at Salt?

“What went wrong was when it was doing so well, Kevin shifted into a, ‘me, me, me, I, I, I’ mindset and it started to make everyone mad,” Holly Sousa says.

Even in those two years of jobbing around prior to Salt of the Earth, there were signs of what was to come. He briefly performed an a la carte version of Alchemy at the former Red Room in East Liberty in 2008. In 2009, he was invited, “no risk,” to take over the kitchen at the former Yo Rita on the South Side.

From our December 2009 review: “Within a few weeks, they had cleaned house. The menu was scrapped … New cooks were brought in. ‘Real cooks,’ says Sousa.” He went on to say he was “in for the long haul.”

Just a year later, Eric “Spudz” Wallace was Yo Rita’s executive chef; by 2012 Sousa was no longer involved with the restaurant.

“He’s hurt a lot of people. And he’s left a lot of people to control his messes,” Cruze says.

In 2012, Sousa began working on two new projects, Station Street Hot Dogs and Union Pig and Chicken. He promised to remain an integral part of the Salt team, telling the Tribune-Review the day after Station Street opened: “If Station Street Hot Dogs had been somewhere else, it wouldn’t have even crossed my mind … I wouldn’t have even entertained the idea of doing it. But, since it’s so close, and I’m pretty invested in the ‘206 — all three restaurants are in the same ZIP code — what’s the worst that could happen? I sleep a little bit less or work a few more hours a day.”

Sousa continued to take a salary at Salt of the Earth, but multiple sources confirm that he was almost entirely absent from that building once he started working on the new establishments.

Cruze says that as investors, she and Doug Cruze dove into what they did best — the design, building and maintenance of the space. But as far as the day-to-day operations of the restaurant, “We were hands-off to a fault. We weren’t micromanagers.”

As things devolved, Cruze says she and her husband stopped going to the restaurant. “We disliked dealing with him that much. It wasn’t a great situation.” They bought Sousa out in 2014 by assuming the URA loan he received when preparing to launch Salt of the Earth. “It was a big effort to extricate ourselves from him,” she says.

“I really want to leave it behind. Life is much better without him,” Cruze adds.

Salt of the Earth closed a year later.

Cruze says that they were in topsy-turvy shape financially when they closed Salt of the Earth, with a few lingering debts to pay, as well as a mortgage and utilities on an empty building until it sold in 2016. In September 2018, restaurateurs Richard DeShantz and Tolga Sevdik opened Fish Nor Fowl, their sixth restaurant to date, in the building.

Disunion

The last time Sousa opened two restaurants simultaneously, they caused the largest amount of financial ruin. Union Pig and Chicken and Station Street Hot Dogs aimed to hit a more casual crowd than Sousa was catering to at Salt of the Earth.

Sousa received some pushback about these concepts, particularly Union Pig and Chicken. The restaurant specialized in barbeque and fried chicken — foods that have significant, long-standing cultural and historical ties to Black foodways in the United States. Someone with Sousa’s celebrity chef status, with easy access to bank loans and institutional financing should have done better to acknowledge community concerns of his opening shop in a predominantly Black neighborhood on the brink of gentrification. And, in retrospect, perhaps such funding should go to someone already living in those neighborhoods interested in operating a restaurant.

This time, he and Holly Sousa were the sole proprietors of both businesses, which they called the 1117 Group. They received a loan from the East Liberty Development Corp. as well as a loan from a family member.

Holly Sousa says that while many of her debts now are paid off or settled, she retains more than $450,000 in liens, including one on the former couple’s Polish Hill house, which she can’t sell. “I don’t want to come off as a disgruntled ex-wife. I was a business partner. I co-signed all of those loans,” she says.

Union and Station Street were very good places to eat and drink and were crowd-pleasers. The income never seemed to catch up with the debts however. “There are people who are very good chefs and very good business people. Kevin isn’t one of them. He’s a very good chef; nobody can really dispute that,” says Jessica Keyser.

Keyser was hired as Union’s opening general manager but soon was named director of operations for the restaurant group (which, technically, wasn’t a restaurant group, as the Cruzes were not affiliated with the other two establishments). She said that debts started to compound almost immediately due to high food and labor costs as well as rent payments and money owed to various vendors and lenders. “Even though Station Street served a very good hot dog — a ‘Kevin Sousa hot dog’ you couldn’t find anywhere else — you can only charge so much for a hot dog. It doesn’t matter how much work goes into it,” she says.

According to Keyser, it didn’t seem to matter to Sousa that the finances weren’t working. “Back then, there was always money for the asking. It’s pretty remarkable how he made it work,” she says.

“It always shocked me that there was always someone waiting in the wings when he needed an influx of cash and nobody ever asked to see what, for me, were the most basic finances,” she adds.

Keyser says that Sousa didn’t want to delve into the nitty-gritty of day-to-day operational costs and he never asked for help managing the financial aspects of the business until it was too late to do anything but dig a deeper hole to get out of the hole that needed immediate filling.

Another, now familiar, pattern was emerging, too. She says Sousa would breeze in and out of Union and Station Street but wasn’t scheduling himself to work for any period of time at either establishment. “He always had an excuse to not be there,” Keyser says.

Sousa was already at work on a restaurant project in Braddock. Not that one. We’ll get to Superior Motors in a bit.

A Less Popular Braddock Tale

Sousa’s vision for a Braddock restaurant goes back to 2011, when he first toured the Pittsburgh suburb with then-mayor John Fetterman (Fetterman now is the lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania). In June 2012, Sousa, at a press conference with Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, announced plans for a restaurant in Braddock called Magarac. He said he and his family were going to live in the old Ohringer home furniture building when the restaurant, which would in large part be funded by foundation and public grants, opened in 2013. He was offered two years of free rent for the restaurant by the building’s then-owners, Heritage Community Initiatives, too.

“A lot of people tell me I’m crazy,” he tells the Post-Gazette in a June 2012 story. “But they thought that about Salt being in Garfield, and a white kid doing BBQ and my opening a hot dog shop across the street from what used to be one of the worst projects in the city.”

Sousa goes on to say that he’s “not going there to turn a buck” and that he “wants to be part of something from the ground up. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” There are promises about working with farms and making it affordable for the Braddock community, in particular a small takeout window where he would serve hot dogs, barbecued chicken and ribs. In the end, the reason given was that the renovation was too costly to pull off.

For Sale

Keyser purchased Union Pig and Chicken from Sousa in January 2015. “He was fast to do the sale. He wanted to get out. He didn’t want cash, he just wanted me to assume all the debt so that he could leave,” she says.

There were thousands of dollars of back rent and debts to vendors outstanding. On top of that, Keyser says there was nearly $60,000 of unrevealed outstanding federal and state payroll taxes that were discovered six months after she took control of the operation. All-in-all, Keyser estimates she was on the hook for somewhere between $250,000 and $300,000.

Keyser closed Union Pig and Chicken in November 2016. She says that most of the private and institutional debt is either paid or settled, but she’s still sorting through much of the tax burden. The second floor of the former Union Pig is now a yoga studio; the first floor sits vacant.

Station Street’s owners faced similar, though not quite as deep, debts when Sousa closed that business at the end of 2014. Robert and Ruth Tortorete, who owned the building and rented it to Sousa, loaned money to the chef so that he could purchase equipment. They eventually sued for approximately $60,000 in back rent, cleaning fees and the unpaid loan. Holly Sousa says that outstanding debts are now paid off. The Fire Side Public House now occupies the building.

A few months after Sousa’s departure from his first three projects, he was moving full steam ahead with his biggest one to date, Superior Motors.

Braddock, Redux?

Sousa’s Kickstarter for Superior Motors, which set a national record at the time for the largest amount of money raised via a crowdsourcing campaign, came with a lot of promises about building a “community-based ‘ecosystem’ that combines food, farming, art, history, industry, training and lodging.” (Note: I donated $25 to this campaign.)

Then-Mayor Fetterman helped “the restaurant ecosystem” raise funds via a nonprofit, Braddock Redux, which received loans and grants from nonprofits including Enterprise Zone Corporation of Braddock, The Heinz Foundation and The Laurel Foundation. Fetterman also offered a lifetime guarantee of free rent for Superior Motors (he and his wife, Giselle, own the building — a former car dealership — and their family lives in the upstairs apartment).

Superior Motors garnered national attention in the digital food magazine Eater, which ran a long piece on Sousa’s promises for Braddock.

And then the chef fell silent, leaving many of his Kickstarter backers and a cadre of eager diners, as well as those who believed in Braddock, wondering what was going to happen next.

Despite the Kickstarter funds and money lined up from other sources, Sousa in earlier interviews acknowledged that the project likely was underfunded from the get-go, and when construction began the building was in significantly worse condition than anticipated.

The delay wasn’t Sousa’s fault, though he could have been more forthcoming about the reasons for it. Instead, Sousa, in an interview with a Pittsburgh-based digital agency called Carney, blamed a March 2015 story in the Post-Gazette that examined Sousa’s shaky financial history in relation to the Kickstarter campaign. In that interview, Sousa dismissed the story as “just filling content, and it was above [the fold] on a Sunday” and “just innuendo without any substance,” despite the fact that it was an investigative article based on data, court cases and interviews.

Superior Motors could have ended there, but an investment group led by the lawyer Gregg Kander stepped in. He and his group secured the funds needed to get Superior Motors back on track and it opened in 2017.

It was a hit. Tables were packed. Toasts were made. Pittsburgh Magazine named the spot our Best New Restaurant of 2018. Time Magazine lauded it as one of its 100 World’s Greatest Places in 2018. Food & Wine Magazine named it as one of its Best Restaurants of 2018. The late writer Anthony Bourdain devoted two segments, more air time than any other location, to Superior Motors in his 2017 “Parts Unknown” Pittsburgh episode.

The Buhl Foundation contributed a $10,000 grant to help build a new pizza oven replacing the slightly dilapidated but functional community oven that had long served the Braddock community. Sousa planned to use the oven as an expansion for the restaurant in the form of a pizza operation called Parts & Service.

The perception in Braddock was that Superior Motors was staking a claim to the space, which for years was used as a gathering spot for community functions. “It didn’t feel like it was ours any longer. It felt like we were getting kicked out of a community space,” says Mary Carey, art, culture and information facilitator at the Braddock Carnegie Library and a community leader. “There were these unprecedented rules [for the oven] we weren’t aware of or talked to about.”

Chris Clark, former general manager of Superior Motors, says there was a Google calendar shared among various organizations, including the restaurant, the library and Barebones Productions (its theater shares the building with Superior Motors).

“We didn’t commandeer it by any means. When you have something that’s yours all the time and then you’re sharing it, it might feel like it’s less available. It took coordination,” says Clark, now a partner in Mount Oliver Bodega and Arlington Beverage Club.

The pizzeria never took root, but the idea of Superior Motors serving as a gatekeeper to accessing the oven exacerbated tension with residents of Braddock. “They were never committed to the community. It was all for show,” says Carey.

A major part of that commitment — as well as a portion of the foundational funding — was to train and hire Braddock residents, including young people in the community.

“I thought it was going to be a great experience for these kids. They were going to come to Braddock and give these young boys a chance to have jobs,” says Pam Sanford. Her son, Daryl Williams would eventually be employed as a high school student as part of the restaurant’s jobs training program. “He was so excited about the job and the people he was going to meet.”

Superior Motors did indeed make an effort to hire at least some of its staff from Braddock and some of those hires became full-time employees at the restaurant. Clark says that worked to achieve a goal of hiring as much as 60 percent of the staff from the community and that he feels “we were there much of the time.” (In my December 2017 review, Clark estimated that 30 to 40 percent of the staff were residents of Braddock.)

“We were one of the only places in Braddock that were hiring people with barriers to entry,” he adds.

Clark says the first cohort of the training program was comprised of eight local hires (four of whom finished). They spent mornings receiving instruction, primarily from Sousa or Clark, in everything from developing pricing structures for drinks to how to quenelle ice cream and then worked in the restaurant in the evenings. “We covered everything you would need to know to be a triple-threat in the service industry,” he says.

In February 2020, Clark began interviewing candidates for a new 12-week course; it never could launch because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to some Braddock residents, however, the jobs training program didn’t come close to fulfilling its stated goals. “I was working there not even a week when the whole group of us got terminated. They didn’t give us any reason, they just told us to turn our uniforms in,” says Ahmad Williams, who was in high school when he participated in the program.

“As many as they hired, they fired. They paid them $200 for the week and that was that,” says Sanford. Sanford explains that her son, for example, was fired as a no-call-no-show, but that he had never been properly scheduled to begin with.

“I’m not going to speak to any individual case. I don’t think it would be fair at all to discuss that,” Clark says.

Williams, Sanford and Carey all report that lines of communication between Superior Motors management, including Sousa and Clark, were virtually nonexistent. “This was this new kind of restaurant with food they had never tasted before. But they wouldn’t take the time to help them learn what they were doing. It’s like they were setting them up for failure,” says Carey.

A New Act?

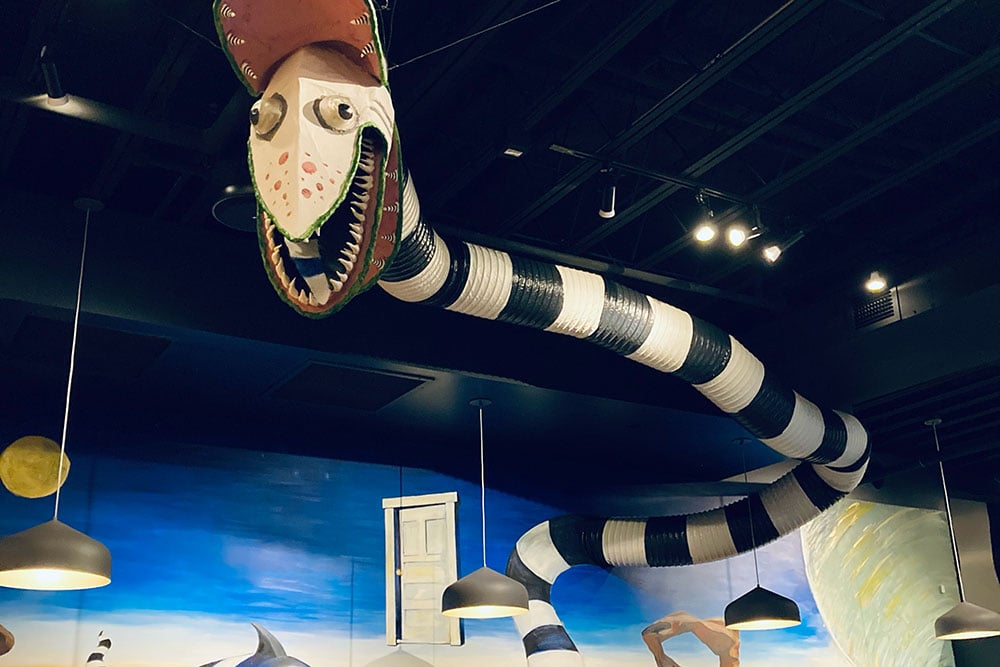

OUTSIDE SUPERIOR MOTORS IN AUGUST, 2021. THE RESTAURANT HAS BEEN CLOSED FOR 16 MONTHS | PHOTO BY RICHARD COOK

The onset of COVID-19 and subsequent lockdown caused Superior Motors to close in March 2020.

Management organized a GoFundMe campaign that netted about $20,000 to support the restaurant’s staff. Superior Motors also received at least $190,000 from the federal Paycheck Protection Program in its first round of grants and loans. Kander says they took the PPP finances as a loan rather than as a grant and that some of the money went to pay Allegheny County and Enterprise Funds loans and the “lion’s share” is still held in a bank account as a loan. “There’s no scandal here. No money went into anybody’s pocket,” says Kander. “I don’t want him [Sousa] to be wrongfully blamed for this. It’s not like he took the money.”

Sousa was already off working on other projects prior to the pandemic. It didn’t get much attention at the time, but he announced Arlington Beverage Club in December 2019.

“We’re two years into Superior Motors and Kevin starts talking about doing another project. And I’m like, ‘you’re kidding me. No. I’m not co-signing any more loans,’” Holly Sousa says, citing his stated commitment to staying in Braddock long-term. The couple divorced in 2020. “He said, ‘I’m going to do what I’m going to do. And if you don’t do it with me, I’ll find someone else.’”

Kander wasn’t interested, either, preferring to deepen his commitment to Braddock, where he currently is focused on the restoration of The Ohringer Arts building, located a half mile from Superior Motors on Braddock Avenue. Sousa found a partner for the Arlington project with Joe Calloway, a South Hills native who runs the real estate investment company RE360.

The oven now is back in the stewardship of the Braddock community. The Braddock Carnegie Library hosted a poetry and pizza night in late July and more events are in the works for the future. The space, equipment and opportunity remain to build on the foundations of the training program at Superior Motors, too. There are plenty of talented and dedicated hospitality industry professionals in the region to lead it, as well as a backer in Kander who seems sincerely devoted to Braddock.

Kander says there is a second chapter for Superior Motors in the works, though it’s too soon to say specifically what it will be. He adds that although there are some outstanding debts to “people who believed in us, and we are committed to paying them,” the restaurant otherwise is on solid financial footing.

“I do agree it’s terrible he can’t hang in there and grind. And I’m sure there is going to be some negative backlash. But so much good has come out of this project and that’s how I prefer to think about it,” he says, citing the holistic community development he sees happening in Braddock.

John Ellis, vice president of communications for The Heinz Endowments — which provided financial support for Superior Motors via Braddock Redux — said in an email, “The restaurant achieved its goals in not only serving as a vibrant and successful asset for the neighborhood, but also in fulfilling its mission to provide training and employment, primarily for people living in the community, and in supporting a number of other local enterprises including a 10-acre urban farm … While we are disappointed to learn that Kevin Sousa has left the project, we hope that the owners of the restaurant are successful in their plans to reopen at the earliest opportunity.”

Braddock’s current mayor, Chardaé Jones, found out that Superior Motors wasn’t going to reopen with Sousa at the helm when she read the Post-Gazette article announcing Sousa’s new endeavors. It prompted her to write a blog post where she looks at Sousa’s promises for Braddock and questions the chef’s sticktoitiveness. “I saw a pattern, and that made me write the piece that I wrote. He didn’t fulfill his mission that the original Kickstarter set out to do,” Jones says.

In it, she ponders if Mount Oliver and Arlington will in a few years find themselves in the same place as Garfield, East Liberty and Braddock.

“Now that Sousa has distanced himself from yet another project, my questions are,” she writes, “what happens when he gets bored again? Does he not realize that his decisions affect jobs in these communities that he briefly invests in, and what was he doing all this time if he wasn’t inspired by food? If I was a community and saw this pattern I would have trust issues and ask for more investment in the form of what value are you adding to a community beyond food? It’s easy to gather people, but it is incredibly hard to build community.”

Update: Sousa Left Mount Oliver Bodega two months after it opened.